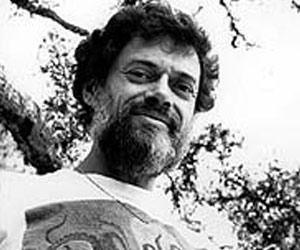

Terence McKenna (1946-2000) was an influential lecturer, writer, and psychonaut who Timothy Leary called “the Timothy Leary of the 90’s.” In McKenna’s obituary in The New York Times, author Douglas Martin sums him up this way: “Mr. McKenna combined a leprechaun’s wit with a poet’s sensibility to brew a New Age stew with ingredients including flying saucers, elves and the I Ching. The essential seasoning was the psychedelic mushrooms that transformed his life and that he recommended — in ‘’heroic doses’ — for virtually everyone.”

Early Influences

McKenna’s interest in the psychedelics and naturally-occurring psychedelic substances was born in the early 1960s when he read several books including Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell. In 1965, he began studying art history at the University of California, Berkeley. He eventually earned a bachelor’s degree in ecology, shamanism, and conservation of natural resources in 1975 from the same institution. The years spanning his formal education were filled with travel and discovery which would shape the course of his life.

McKenna traveled to Nepal in 1969 to learn first-hand about the shamanic use of psychedelic plants. During his time there he studied the Tibetan language and also became a hashish smuggler until one of his shipments was seized by US Customs. Needing to move on, he went to southeast Asia where he toured old ruins and became a professional butterfly collector.

Life-Changing Travels to South America

In 1972, McKenna, his brother Dennis, and three of their friends went to the Amazon forest in Columbia, South America. Their quest was to find oo-koo-hé, a plant preparation made by the native people containing dimethyltryptamine (DMT). During their search, they came across openings in the forest with fields of huge Psilocybe cubensis mushrooms. This discovery changed the focus of the expedition.

Terence and Dennis learned the cultivation techniques used by the farmers and brought P. cubensis spores back with them to the United States. Using the knowledge they gained, the spores, and ordinary kitchen implements, they developed a cultivation technique that anyone could follow to grow the mushrooms. Up until that point, no one had figured out how to do it. This marked the first time laypeople could produce entheogens in their own home.

The McKenna’s efforts culminated in their landmark 1976 book Psilocybin: Magic Mushroom Grower’s Guide which they authored under the names O.T. Oss and O.N. Oeric. In 1975, the brothers published The Invisible Landscape: Mind, Hallucinogens, and the I Ching which was inspired by their trip to the Amazon.

In 1985, Terence McKenna along with his wife Kathleen founded Botanical Dimensions, a non-profit preserve on Hawaii’s Big Island dedicated to collecting, protecting, and propagating plants with ethnomedical significance. Part of the preserve’s work includes maintaining a database on the purported healing properties of the plants.

The Stoned Ape Hypothesis

Another important book McKenna wrote was his 1992 Food of the Gods: The Search for the Original Tree of Knowledge A Radical History of Plants, Drugs, and Human Evolution. In this book, he explains his “stoned ape hypothesis.” McKenna says P. cubensis contributed to the increase in brain size and capabilities of early human ancestors, leading to the evolution of Homo sapiens.

McKenna explains that as Africa began to undergo desertification, human ancestors were forced out of the forests and onto the savannas to find food. These groups would follow footprints and dung on the ground to find animals to hunt and eat. It just so happens the hallucinogenic mushroom Psilocybe cubensis is a dung-lover and often found growing in the manure of animals that live on the savanna.

According to his stoned ape hypothesis, human ancestors ate these mushrooms and experienced their extraordinary hallucinogenic effects. The effects are often described as “mind-opening,” feeling empathy and increased courage, and seeing fractal patterns even with the eyes closed. After consuming the mushrooms, leaders emerged within groups as those who were brave and kind to others. These leaders became trusted as looking out for their best interests by other group members.

McKenna’s theory goes on to propose that psilocybin mushrooms improved visual acuity, making individuals better hunters. More food meant a higher rate of reproductive success. Although there is no scientific proof, McKenna also thought higher doses of psilocybin would increase sexual arousal, resulting in more mating attempts. He also proposed that higher doses would increase activity in the language-forming regions of the brain, causing visions and music.

Further, McKenna said the strange effects of psilocybin dissolved the ego and contributed to the development of religion. So, the theory argues access to hallucinogenic mushrooms was an evolutionary advantage for humans. McKenna called it the ‘evolutionary catalyst.’

McKenna died in 2000 of brain cancer at a friend’s home in San Rafael, California at the age of 53.

More information on Terence McKenna is available through his entry on Wikipedia.