Psilocybin is the most well-known compound found in psychedelic mushrooms (aka psilocybin mushrooms or magic mushrooms). It is a substituted tryptamine and prodrug of psilocin, and the compound that is responsible for eliciting psychedelic effects. Psilocybin is a chemical analog of the neurotransmitter serotonin. It occurs naturally several species of magic mushrooms along with psilocin and other compounds. Psilocybin and psilocin were first synthesized by Albert Hofmann and his research team including Franz Troxler, in 1959.1

There are several psychoactive molecules in magic mushrooms. Psilocybin is most frequently cited as “the” active component in magic mushrooms. However, this is a common misconception. Technically, psilocybin is a prodrug of psilocin. When consumed, psilocybin is rapidly metabolized into psilocin. The data from receptor binding studies shows that psilocin is the primary bioactive psychoactive component based on its binding affinity at the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor (Table 1). Magic mushrooms naturally contain some psilocin but it is found only in minimal amounts.

Table 1: Binding affinities for psilocybin and psilocin at serotonin receptors.2

| Receptor | Psilocybin Ki (nM) | Psilocin Ki (nM) | Species |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | >10,000 | 49.0 | human |

| 5-HT1B | >10,000 | 219.6 | human |

| 5-HT1D | 2,119 | 36.4 | human |

| 5-HT1E | 194.8 | 52.2 | human |

| 5-HT2A | >10,000 | 107.2 | human |

| 5-HT2B | 98.7 | 4.6 | human |

| 5-HT2C | >10,000 | 97.3 | rat |

| 5-HT3 | >10,000 | >10,000 | human |

| 5-HT5 | 6,181.0 | 83.7 | human |

| 5-HT6 | 413.5 | 57.0 | human |

| 5-HT7 | 597.9 | 3.5 | human |

Several genera of magic mushrooms contain psilocybin and psilocin including Inocybe, Conocybe, Panaeolus, Gymnopilus, and Pluteus.3 However, psilocin is not the only psilocybin derivative in magic mushrooms. Others include norpsilocin, baeocystin, norbaeocystin, and aeruginascin. The derivatives and amounts present vary in different parts of the mushroom. They also vary in between species and even within batches of the same species. Because of their close metabolic relationship, psilocybin and psilocin are often discussed together.

The Chemistry of Psilocybin

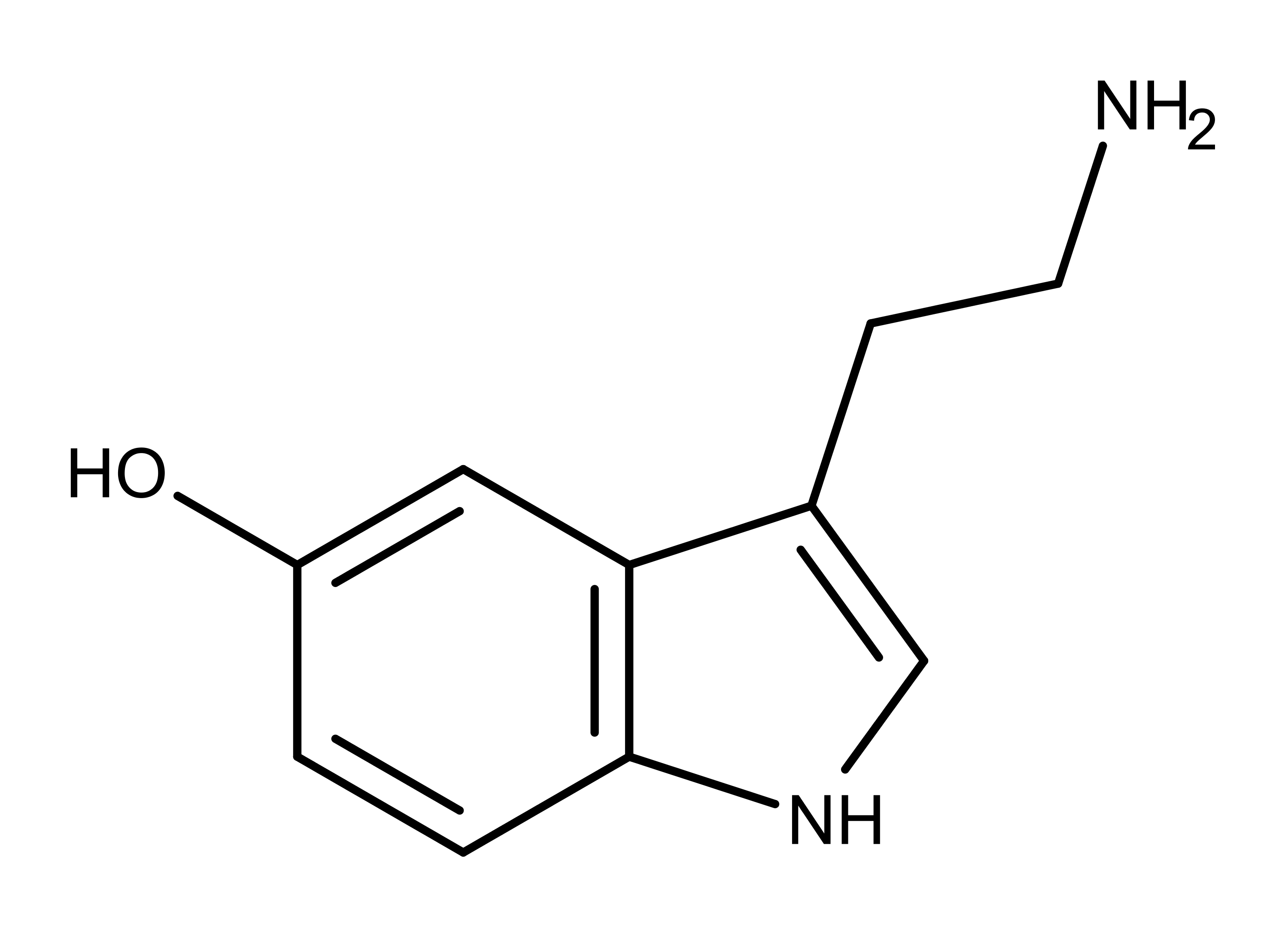

Psilocybin and psilocin (Figure 1) are tryptamine alkaloids and structural analogs of the neurotransmitter serotonin (Figure 2). Serotonin is known as the “happiness molecule” or “confidence molecule” because it produces feelings of well-being when it binds to specific serotonin receptors. Serotonin receptors in the brain are the primary targets for magic mushroom compounds. But even though magic mushroom compounds bind to the same serotonin receptor, they cause different effects than serotonin. So the ‘magic’ is at least partially due to different molecules = different drugs with different binding properties.

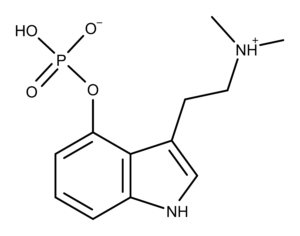

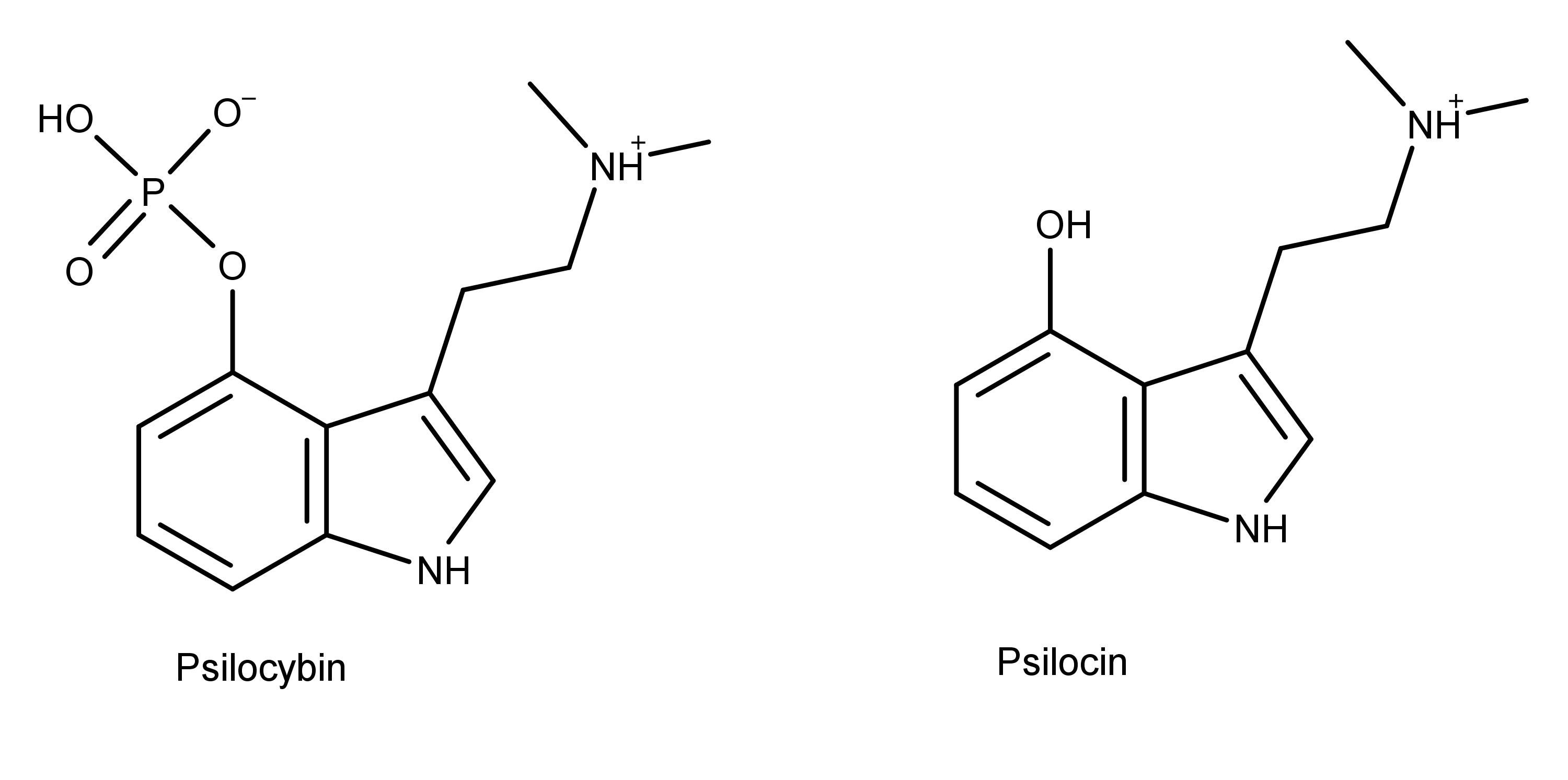

Figure 1: The chemical structures of psilocybin and psilocin.

As the chemical structures in Figure 1 shows, psilocybin and psilocin differ from each other at position 4, having a phosphate and hydroxyl group, respectively. As structural analogs of serotonin, both compounds differ from serotonin by having two methyl groups on the amine group on carbon 3. Also, the substituent groups on the benzyl ring of psilocybin and psilocin are in position 4, while the hydroxyl group of serotonin is in position 5.

The Pharmacology of Psilocybin

Psilocybin is a prodrug of psilocin. This means the prodrug psilocybin undergoes changes in the body which convert it into the active form, psilocin. Specifically, a chemical process called dephosphorylation removes the phosphate group on psilocybin, creating psilocin.

The dephosphorylation of psilocybin occurs in two ways in different areas of the body.4-6

- The acidic environment in the stomach is a favorable environment for the rapid dephosphorylation of psilocybin.

- Enzymes such as alkaline phosphatase and other non-specific esterases dephosphorylate psilocybin in the intestines, kidneys, and the blood.

The phosphate group on psilocybin in Figure 1 is highly polar. This polarity along with the positively charged amine group makes the molecule zwitterionic and more soluble in water than psilocin.7 Without the phosphate group, psilocin becomes more lipid-soluble than psilocybin, making it metabolically available in the body and more easily absorbed in the intestines.

At this point, psilocin is distributed all over the body via the bloodstream. Being lipid soluble allows psilocin to cross the blood-brain barrier and elicit its effects. Researchers can detect psilocybin and psilocin in human blood plasma 20-40 minutes after oral administration of psilocybin.5,8 They find maximum levels in the blood 80-105 minutes after administration.

About 80% of metabolized psilocybin gets excreted in the urine as a compound called psilocin-O-glucuronide (Figure 3).9-11 Some psilocin and psilocybin (only 3-10%) are excreted in the urine, mostly in a conjugated form with glucoronic acid.8,11

The Applications and Potential of Psilocybin

Outside the body, psilocin is a short-lived and unstable molecule.12 Therefore applications involving the use of psilocin are accomplished by administering its precursor, psilocybin.

Psilocybin is being studied in mental health via what is termed psilocybin-assisted therapy. Therapies using synthetic psilocybin alone and only dried magic mushrooms have attracted attention as potential therapeutic agents.

Studies using synthetic psilocybin-assisted therapy have found:

- Psilocybin is safe and effective for treating treatment-resistant depression (TRD).13

- Psilocybin works for treating TRD by reviving emotional responsiveness in the amygdala.14

- Psilocybin produces lasting changes in attitudes and beliefs including increased nature-relatedness and decreased authoritarian political views.15

- The quality of the psychedelic experience using psilocybin is essential for long-term positive changes in mental health.16

The results of these studies have been so encouraging that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has given breakthrough therapy designation to psilocybin for use in TRD. Other studies demonstrating the therapeutic applications of synthetic psilocybin include:

- A single dose of psilocybin is effective in providing “rapid, robust, and enduring” anti-depressant and anti-anxiety effects in patients with life-threatening cancer.17,18

- Psilocybin may be an important adjunct for the treatment of tobacco addiction.19

- Psilocybin may be useful in treating alcohol dependence.20

Psychotherapists Tom and Sheri Eckert founded the Oregon Psilocybin Society (OPS) to advocate for the legalization of using dried psilocybin mushrooms in therapy. Their efforts center around the Psilocybin Service Initiative (PSI2020). This ballot petition allows for psilocybin mushroom services throughout Oregon, including psilocybin mushroom-assisted therapy. If passed by Oregon voters, this effort will also reduce the criminal penalties for possession of psilocybin mushrooms in Oregon to a violation.

Dose Data

| Dose (mg/kg) | Administration | Species | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD50 | 275 | Intravenous | Mouse | 22 |

| LD50 | 420 | Intraperiotoneal | Mouse | 22 |

| LD50 | 12.5 | Intravenous | Rabbit | 23 |

| LD50 | 280 | Intravenous | Rat | 23 |

| TDLO | 0.060 | Oral | Human | 24 |

| TDLO | 0.037 | Intraperiotoneal | Human | 24 |

Receptor Binding Affinity Data

| Receptor | Ki (nM) | Species | Note | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | >10000 | Human | 2 | |

| 5-HT1B | >10000 | Human | 2 | |

| 5-HT1A | 2119 | Human | 2 | |

| 5-HT1E | 194.8 | Human | 2 | |

| 5-HT2B | >10000 | Human | 2 | |

| 5-HT2B | 98.7 | Human | 2 | |

| D1 | >10000 | Human | 2 | |

| D2 | >10000 | Rat | 2 | |

| D3 | >10000 | Rat | 2 | |

| D4 | >10000 | Rat | 2 | |

| D5 | >10000 | Rat | 2 |