This biography provides a summary of Dr. Richard Schultes’ life and work, sourced significantly from a 2001 New York Times obituary by Jonathan Kandell.1

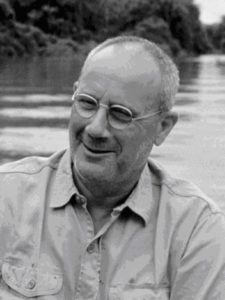

Dr. Richard Schultes was a famed botanist, conservationist, Harvard professor, and expert on psychoactive plants. He is commonly referred to as the “father of ethnobotany.”

Dr. Schultes was born in Boston in 1915 to working-class German immigrants. His passion for botany ignited when bedridden with an illness as a child, his parents read to him Notes of a Botanist on the Amazon and the Andes, a 1908 travel diary by naturalist Richard Spruce. He went on to study biology at Harvard, receiving his Bachelor’s degree in 1937, his Master’s in 1938, and his Doctorate in 1941 from the university, according to The Harvard Gazette.

A memoir of Dr. Schultes by Luis Sequeira describes the ethnobotanist’s research in the late 1930s: Dr. Schultes studied peyote in the southwestern United States for his dissertation, as well as the hallucinogenic (psilocybin–containing) teonanácatl mushrooms and ololiuqui plant (morning glory) in southern Mexico.2,3 In 1936, he lived for several weeks with the Kiowa tribe in the modern midwest United States and participated in their peyote ceremonies.

Upon graduating with his doctorate, Dr. Schultes focused his ethnobotanical research on the Amazon rainforests, mostly in Colombia. He traveled the region from 1941 to 1953, studying more than 2,000 medicinal plants used by native Amazonians. He also collected specimens from rubber trees for the United States Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Plant Industry, an assignment initiated by wartime need. Today’s field botanists still use Dr. Schultes’ preservation method of soaking plant specimens in formaldehyde before pressing them between sheets of newspaper. WBUR reported in March 2021 that Massachusetts General Hospital’s new Center for the Neuroscience of Psychedelics would, among other endeavors, use advanced technologies such as DNA barcoding and stem cells to research many plant specimens Schultes collected during his time in the Amazon.

Dr. Schultes took a rustic approach to his research ventures, traveling via simple aluminum canoe and relying mainly on staple foods from native hosts. He was reverent of indigenous populations, documenting the integral role of psychoactive plants in their lives, consulting local shamans about various species, and trying many of the medicinal plants himself at the offering of his hosts. In 1988 he wrote, “the accomplishments of the aboriginal people in learning plant properties must be a result of a long and intimate association with, and utter dependence on their ambient vegetation. This native knowledge warrants careful and critical attention on the part of modern scientific methods.” 4 He also warned of the destruction and shrinkage of rainforests due to expansion of exploitative industry and agriculture, writing in 1994: “The Indian people and their knowledge are disappearing even faster than the plants themselves.” 5

Dr. Schultes was the first person to scientifically study ayahuasca. He identified that in addition to a vine known as Banisteriopsis caapi, the brew contained plants called Psychotria viridis, or Chacruna, and Diplopterys cabrerana, or Chaliponga, which contain DMT. He surmised, correctly, that the tea’s unique orally-active psychotropic potency was due to the interaction between the DMT and the monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) enzymes present in B. caapi.6

Dr. Schultes returned to the US in 1953. An obituary in The Harvard Gazette reported his many roles at the university: he became curator of Harvard’s Orchid Herbarium in 1953, then served as curator of economic botany beginning in 1958. From 1967 until 1985 he directed the Harvard Botanical Museum, commencing his professorship at the university in 1970. He went on to become professor emeritus in 1985.

Much of the psychedelic revolution in the 1960s was influenced by Dr. Schultes’ research. Unlike many contemporaries inspired by his work, however, he did not glamorize psychedelia and was instead concerned with the medicinal value of the plants he studied and considered sacred. He allegedly ridiculed Timothy Leary for misspelling Latin names of psychoactive plants and ragged on William Burroughs for his dramatic description of a profound psychedelic trip, replying, “That’s funny, Bill, all I saw were colors.” In 1979, Dr. Schultes helped coin the term “entheogen” — referring to psychoactive substances whose use are spiritual in nature — with other scholars including Jonathan Ott, R. Gordon Wasson, and Carl Ruck.7

From 1962 until 1980, Dr. Schultes was editor of the scientific journal Economic Botany. Within the same decades, he served on the Editorial Board of several other publications including Horticulture, Social Pharmacology, Journal of Ethnopharmacology, and the Journal of Latin American Folklore. Dr. Schultes wrote more than 450 scientific articles and authored or co-authored 10 books, including Hallucinogenic Plants (A Golden Guide) (1977), Vine of the Soul: Medicine Men, their Plants and Rituals in the Colombian Amazonia (1992), The Botany and Chemistry of Hallucinogens (1992), and Plants of the Gods (1973). The latter two were written with the late Dr. Albert Hofmann.

Dr. Schultes earned many honors before he passed away in 2001, including a gold medal from the Linnean Society of London, a gold medal from the World Wildlife Fund, the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement, the Lindbergh Award, and a Harvard Medal.

More information about Dr. Schultes’ work can be found on his ResearchGate profile.