Note: The author of this article, Mario de la Fuente Revenga, was a colleague and personal friend of Jordi Riba. Dr. de la Fuente Revenga writes this article using that perspective.

Layering the Bricks for the Renaissance of Psychedelic Research

Some of the most paradigmatic examples of what we know as classic psychedelics (i.e., psilocybin, mescaline, bufotenin) come from natural sources that have been used by different groups of people since the dawn of time. The basis of our scientific knowledge on these psychoactive substances starts with the observation of the ritualistic use of plants and fungi in shamanistic societies, followed by the careful and systematic isolation and identification of the components responsible for their effects on the human psyche.1

Jordi Riba, a turn of the millennium ethnopharmacologist, devoted most of his research career to the study of ayahuasca. With the support of his mentor, Manel Barbanoj, he conducted at the Sant Pau Institute for Biomedical Research (Barcelona, Spain), the first controlled clinical study featuring this Amazonian plant-based psychedelic brew in the late 90s一laying the foundation of our current knowledge of its clinical pharmacology.2

The Bumpy Road of Psychedelic Research

An article published in a scientific journal is a very poor representation of the hurdles that one had to be overcome to make it possible. Jordi Riba’s initiation on the study of ayahuasca was not a smooth ride. He faced initial resistance from religious groups that considered his studies a desecration of their revered sacrament. After the initial setbacks, the same groups, later on, came to embrace his work, helped him out, and even participated in his studies as volunteers.2 However, this is not the only point where Riba found resistance to developing his research plans.

Often lacking in institutional support and under draconian funding constraints, Riba managed to move his research forward and achieved international recognition一all the while, he was virtually unknown in his home country.

Most of Jordi Riba’s scientific career took place at the Sant Pau Institute for Biomedical Research, where he surrounded himself with a small team of close collaborators who accompanied him during his scientific journey. However, his network expanded worldwide; at the moment of writing this piece, his extensive list of peer-reviewed publications accumulate thousands of citations and features as co-authors renowned researchers in psychedelic science from all over the world.3 At the end of his career, his ever-curious mind found a more stimulating environment at the University of Maastricht (Netherlands), where he continued his research over the last few years.

Very early on, Riba took the challenge of translating Jonathan Ott’s Pharmacotheon into Spanish, making it accessible to millions of Spanish speakers worldwide.4 Like Ott’s thorough analysis of psychoactive plants, Riba’s early works are rigorous, very systematic, and somewhat descriptive–making them a hard digest for the inexperienced reader. But it is this kind of groundwork that set the stage for his greater contributions.

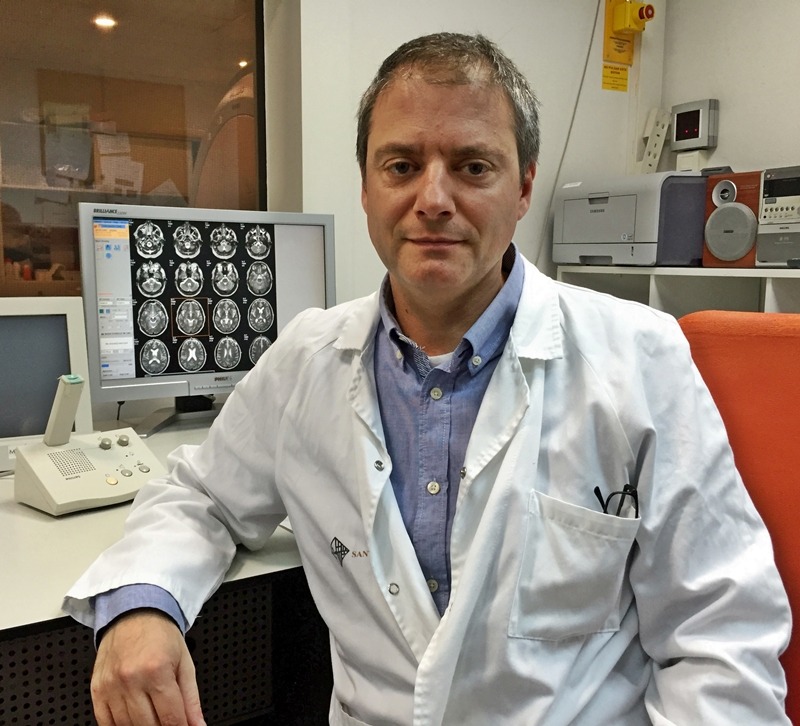

Image from ResearchGate.net

In the last years of his career, Riba engaged in more application-oriented research, addressed more contentious topics, and even founded a small start-up (Blumentech S.L.) to seed the exploration of a therapeutic application for ayahuasca for neurological disorders. Jordi Riba was very connected to his hometown, Barcelona, to the point that he playfully flirted with the idea of registering a mixture of isolated alkaloids under the brand name of “Barnahuasca”.

The Man Behind the Scientist

Riba was by no means someone with an aversion for risk一a certified scuba diver and pilot; he jumped into the water or climbed into the cockpit of a Cessna whenever he had the occasion. He was not blinded by the glittering promise that psychedelics would ever get an approved therapeutic indication for mental health but was up for the challenge. Riba embraced risk一scientifically and otherwise一as well as the uncertainties inherent to his main field of research and career, and yet he found the exploration of the mechanism through which psychedelics manifest their effects fascinating enough to justify every minute of his time at work.

His hard work did not go unnoticed. In 2017 Riba was listed among the top 25 crafters of tomorrow’s world by the Rolling Stone magazine一sharing the stage with tycoon Elon Musk and the United States Senator Kamala Harris.5 With a very optimistic outlook on the future of Riba stated,

I don’t think it will be long before we see psychedelics incorporated into the therapeutic arsenal.

If such a prediction feels closer to being fulfilled than ever, it could be, in part, thanks to his contributions.

Some Final Thoughts

Jordi Riba’s life was cut down short at the age of 51. His extensive and seminal work should be a reminder that psychedelic science stands on the shoulder of giants who, like Jordi, managed to open the path in an unfavorable scientific and societal environment. Riba’s legacy stands alone for its scientific quality, but it is also a reminder that the seemingly dissipating stigma around psychedelic research was once very pervasive. On the bright side, his work is also an open invitation for newer generations to venture into a fascinating field that is taking its first steps into adulthood.

Descansa en paz Jordi.

Cómo murió?