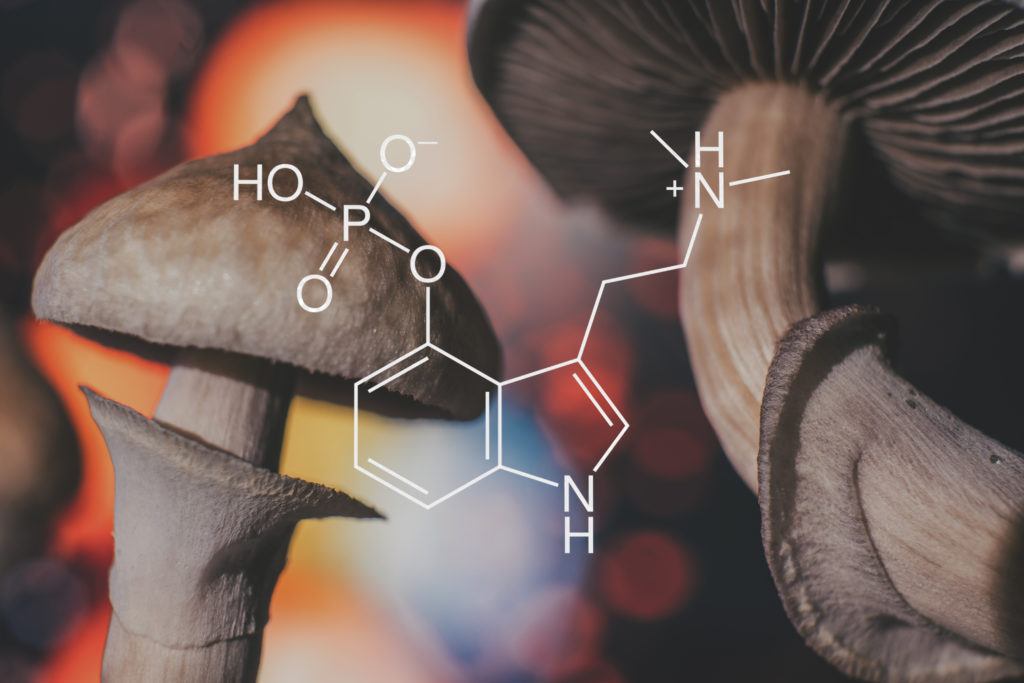

For most of human history, it was the mushrooms themselves that were magic. Then, in 1958, Albert Hofmann isolated and synthesized psilocybin and its metabolite psilocin, and suddenly Western science had an explanation — a specific molecular source — for the peculiar effects associated with ingestion of some wild mushrooms.1 For the first time, one theoretically no longer needed to eat a mushroom to experience these effects. It was a dramatic shift whose full implications are now beginning to come into view.

Although the use of synthetic psilocybin for research purposes began and generally became accepted back in the 1960s, recent developments are accelerating this trend.2 New technologies allow for synthesizing and bioengineering psilocybin more quickly and cheaply than ever before.3-8 And more rigorous research standards make accuracy, precision, and purity even more important than during the first wave of psychedelic research.9

As psilocybin and related drugs become increasingly accepted in our society, it’s easy to imagine an impending spillover from the lab to the living room of standardized, purified preparations and products far removed from their botanical origins.

Growing Mushrooms

Nearly 200 species of fungi contain psilocybin.10 They are endemic to six continents and classified under 13 different genera, the largest and most well-known being Psilocybe.11 Among its 116 species, the most common is Psilocybe cubensis, a native of the southeastern United States, Mexico, the Caribbean, parts of Central and South America, Southeast Asia, and Australia.11

More importantly, P. cubensis is also relatively easy to cultivate.11 As such it has been the key mushroom species — the key source of psilocybin — in modern Western culture for six decades since Hofmann, Gordon Wasson, Terence McKenna, and other figures first brought it to popular attention here.

But could the current wave of psychedelic science, culture, and medicine spell the end of the reign of P. cubensis? Among researchers it essentially already has—and for good reason, some argue.

Single vs. Multiple Compounds

“We’re using the synthetic compound so that we can dose more precisely and also better understand the mechanism of action of that specific compound,” says Emmanuelle Schindler of Yale University, who studies the effects of psilocybin on headache disorders.12

From a scientist’s standpoint it makes more sense to study a single compound at a time. We’re not satisfied with just seeing an effect; we want to understand how.

Adam Halberstadt, an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of California at San Diego who is leading a study into the effects of synthetic psilocybin on phantom limb pain, says that administering any additional compounds from psychedelic mushrooms in modern clinical trials, even if practical and fully legal, would above all represent a liability.

“Using a mixture of isolated mushroom compounds, or a synthetic equivalent, would markedly increase the likelihood of there being some type of problem in the trial,” Halberstadt says. He points to the increased likelihood of adverse drug interactions with secondary compounds, or of negative reactions to multiple mushroom alkaloids among trial participants with low renal function. “Giving multiple tryptamines in combination potentially makes the effect in each subject much more dependent on their unique physiology, meaning a wider range of therapeutic responses in a trial, which is not great. Having more variance can make it more difficult to detect an effect.”

Natural vs. Synthetic

Not everyone believes the industry needs to ditch the mushroom to move forward. In fact, some companies are betting it won’t. Among them is Canada-based Filament Health, which grows large volumes of psilocybin mushrooms at its 3,500-square-foot research and manufacturing facility in Vancouver, British Columbia. The company uses these mushrooms to produce a variety of extracts targeted for use in clinical trials and as “non-pharmaceutical psychedelics” in places like Oregon where psilocybin and related drugs have been decriminalized, says CEO Ben Lightburn.

“We think that in those markets, everyone will prefer a natural product because that’s the product that they’re already familiar with, especially in the case of underground psilocybin therapists,” Lightburn says. Standardized extracts offer the added benefit over whole mushrooms of precise dosing, he suggests. “While a certain amount of variability may be acceptable for personal use, for therapeutic use, it must be consistent. And reliable.”

To date, there’s no evidence that any other compounds in magic mushrooms like baeocystin, aeruginascin, and norpsilocin contribute to improved therapeutic outcomes versus pure psilocybin, no matter the source.

But Filament hopes that through an upcoming phase-one trial at the University of California at San Francisco it will be able to demonstrate the value of its extraction process and the use of botanically sourced drugs with multiple active constituents. The trial will pit two psilocin extracts (one administered orally, the other sublingually) against a comparable psilocybin-based extract to test the hypothesis that those containing psilocin will have a faster onset time, improved consistency, and fewer side effects without sacrificing psychedelic intensity. These extracts contain all of the secondary metabolites that exist naturally in the mushroom, in the same proportion, says Filament director of communications Anna Cordon.

Beyond being noteworthy for its use of naturally sourced mushroom compounds, the trial will be the first to directly administer psilocin rather than its prodrug psilocybin, as to date manufacturers of synthetic psilocybin have not been able to produce a stable formulation of psilocin for use in a clinical trial. The study was approved November 2 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and will be posted on ClinicalTrials.gov, Cordon says.

Advantages and Disadvantages

In a June 2021 presentation to the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board, a governor-appointed body created by the state’s passage of Measure 109 the previous year, celebrity mycologist Paul Stamets offered his own take on the future of the Psilocybe mushrooms he has helped usher to international notoriety in recent years.

“There is a tremendous appeal to the natural form,” he says in his talk. “There is tremendous interest and history in the natural form.” (It’s worth noting that in addition to his roles as a researcher and speaker, Stamets owns a Washington-based company called Fungi Perfecti that cultivates and sells gourmet edible mushrooms.)

There are also disadvantages associated with whole Psilocybe mushrooms, he acknowledges. Beyond variability in psilocybin and psilocin content, there is some risk of contamination, an absence of standards and accountability (so far), and a likely lack of confidence among naive consumers and patients.

“Growing psilocybin mushrooms for food safety takes it all the way to the dried form,” Stamets says. “Once you make an extract of it, now you’ve gone from a natural form to an extraction, and you begin to cross the line into the drug category.” For many in the burgeoning psychedelic industry, including prospective patients and customers, that’s precisely the point.

Interesting read. As a Psychology major, I’m very interested in the therapeutic benefits of psilocybin. I’m curious to read the results from the naturally sourced extracts trial.

How can there be evidence if clinical double blind trials would needed to get that evidence ? — and if ? no such trials are made. Many adecotal experiences suggest that the effects of prilocybin and it’s mono- and normethyl analogs produce wery much diffenrent subjective effects — and also combined with relatively smaller amounts of psilocybin. ” To date, there’s no evidence that any other compounds in magic mushrooms like baeocystin, aeruginascin, and norpsilocin contribute to improved therapeutic outcomes versus pure psilocybin, no matter the source “ z Adam Halberstadt, an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of California at San Diego ” Using… Read more »

Perhaps it’s true that the other compounds are not relevant to the intended effects but I can’t help thinking about terpenes and cannabis. For some years there was significant debate about the potential of terpenes to alter the pharmacodynamic profile of various chemovars, at times researchers call the ‘entourage effect’ bunk. The latest research however is fairly conclusive that terpenes are pharmacodynamically/kinetically relevant even if the implications are not fully understood. It is always easier to design an experiment using a single or isolated number of compounds – THC and CBD for example. This is practical but to thoroughly investigate… Read more »

The issue here is entourage effects and whether they exist in psychedelic mushrooms. The author ignores all previous work done on entourage effects in mushrooms. He categorically says there are no such effects when in fact there are reported findings in animal studies and anecdotal reports in humans. There are no comprehensive studies so the author cannot simply say there are no effects. A more appropriate statement would be that there is some evidence but comprehensive studies are needed. Previous articles in PSR take a more balanced view: e.g. https://psychedelicreview.com/the-entourage-effect-in-magic-mushrooms/ There are other articles in PSR that look at both sides of… Read more »

Hi Bernard, thank you for your comment. Point taken; you are correct about the potential for additional effects associated with these secondary compounds, and about the need for more research. However, the statement as written regarding specifically the current lack of evidence for additional therapeutic benefits is accurate — and this is a key point for researchers studying psilocybin as a pharmaceutical. In addition, just for background, the editor of this piece also wrote the PSR article you cite about the “entourage effect” in mushrooms, so there is a consistent perspective and knowledge base behind them. In any case, thanks… Read more »

I find myself disturbed by seeing an incredible, natural plant medicine stripped of any complexity and reduced to a scientific equation that allows for only one element of the plant (what is assumed to be the “active” ingredient), to be administered and studied at a time. I suppose this “scientific” approach can provide a good amount of data, it seems very clear this approach overlooks the obvious. Namely, that ALL of the compounds in the plant contribute to it’s ability to support and heal us. These mushrooms are a mysterious interweaving of many compounds, evolved by nature over unknown thousands… Read more »