Serotonergic psychedelics – i.e., LSD and psilocybin – show great promise in treating a multitude of neuropsychiatric disorders, in particular depression.1 Many conventional pharmacological antidepressants (ADs) – i.e., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) – target communication via one or more brain neurotransmitters; the chemical messengers in the brain that, among other functions, regulate mood.

Network Effects

Psychedelics appear to exert their antidepressant on a more macro level when compared with conventional ADs, promoting lasting changes in brain networks.2 For example, psilocybin – a prodrug of psilocin found in psychedelic mushrooms (aka magic mushrooms) – acutely decreases activity within the default mode network (DMN), a system of functional connections in the brain that is responsible for introspection and planning. The DMN is formed and strengthened through adaptive responses to life events and experiences, and excessive rigidity of the DMN could be symptoms of rumination, depression, and other mental health conditions.

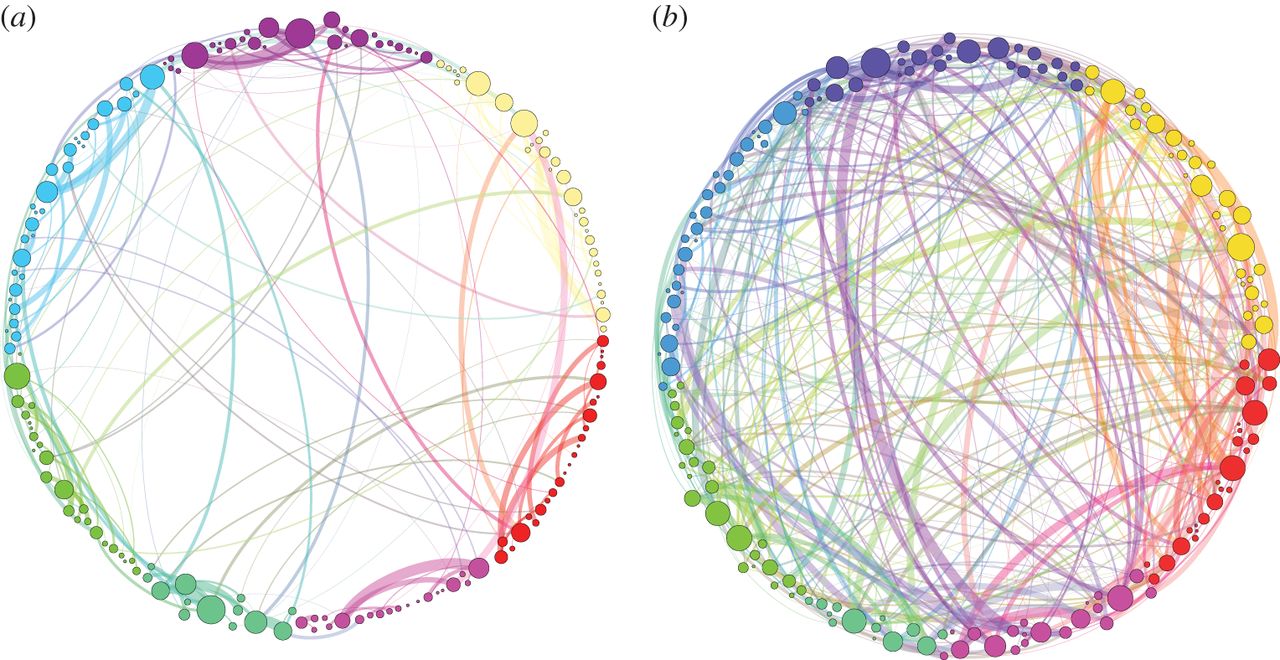

The downregulation of the DMN by psilocybin temporarily leads to increased connectivity between brain regions that usually don’t communicate with each other, corresponding to the subjective experience of “ego-dissolution” and the subsequent generation of new perspectives and insights (Figure 1).2

Figure 1: Simplified illustration of global brain connectivity while receiving the placebo (a) and psilocybin (b).3

Recent research from the Centre for Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London (ICL) examined the activity of a key component of the DMN following psilocybin administration – the amygdala.4,5

The Amygdala and Emotions

The amygdala – associated primarily with the processing of emotional responses, including fear and anxiety – is an almond-shaped brain structure located in the limbic system. Emotional life is primarily housed in the limbic system, and it supports the formation of memories.

The ICL group used Function Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI or brain scan) to investigate the use of psilocybin in depressed patients, demonstrating increased amygdala activation the day after treatment.4,5 Study participants exhibited amygdala hyperactivation while viewing pictures of negative stimuli (in this case, negative facial expressions).

These results conflict with claims that increased amygdala activation to negative stimuli is a hallmark of psychopathology. In fact, conventional antidepressants have been shown to reduce amygdala activation.6

Furthermore, recent research published by Johns Hopkins showed decreases in amygdala responses to negative emotional stimuli one-week post-psilocybin treatment, which aligns with the conventional view of antidepressant action.7

The Prefrontal Cortex: The Orchestrator

Recent research from the Centre for Psychedelic Research shed light on the seemingly counterintuitive hypersensitivity of the amygdala following treatment with psilocybin.5 Again, using fMRI, the study demonstrated a decrease in connectivity between the amygdala and an area of the brain called the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), the day after psilocybin administration. Many implicate the prefrontal cortex in the orchestration of thoughts and actions in accordance with internal goals and planning complex cognitive behavior. The vmPFC, in particular, plays an important role in emotional processing, imparting a top-down inhibitory control on the limbic system, including the amygdala.

The study group posits that this decrease in connectivity results in a reduction in vmPFC inhibitory control of the amygdala, thereby increasing amygdala activity. Decreased connectivity between the amygdala and vmPFC is thought to underlie neuropsychiatric disorders, accounting for disturbed emotional processing.8 Moreover, decreases in connectivity correlated with reduced rumination one week after the dosing session. Rumination, defined as a pattern of recursive self-directed and self-reflective thinking focused on one’s negative emotions, is a significant component of a depressive episode.

Contextualizing the Findings

Results from the studies discussed above challenge the narrative that increased amygdala sensitivity is a core characteristic of psychopathology. One leading explanation from the ICL group for amygdala hypersensitivity following psilocybin administration is that psychedelics exert their therapeutic effect in a novel manner when compared with traditional ADs.

Traditional ADs downregulate emotional responses, effectively blunting emotions, allowing patients to cope with their depressive symptoms. Conversely, psychedelics enable individuals to more fully engage with their emotions, promoting acceptance of said emotions.

However, research into the precise mechanism of action of psychedelic compounds is still in the early stages, and speculation is widespread.

Excellent article!

spread the truth.

Very interesting article! Thanks for sharing!