Aeruginascin is a compound present in some species of magic mushrooms (aka psilocybin mushrooms or psychedelic mushrooms). Structurally, aeruginascin is closely related to psilocybin. However, aeruginascin is seldom mentioned in contemporary or scientific literature. Psilocybin is by far the most discussed compound in magic mushrooms.

It is important to remember that technically, psilocybin is not the active molecule in magic mushrooms. It is a prodrug of psilocin, which is the active molecule. When ingested, psilocybin is readily converted into psilocin, providing the psychoactive effects.

Because of its potential utility in medical treatments, scientists have become increasingly interested in psilocybin and psilocin. Scientists would also benefit from investigating other psilocybin derivatives, such as baeocystin, norbaeocystin, and aeruginascin.

What is Aeruginascin?

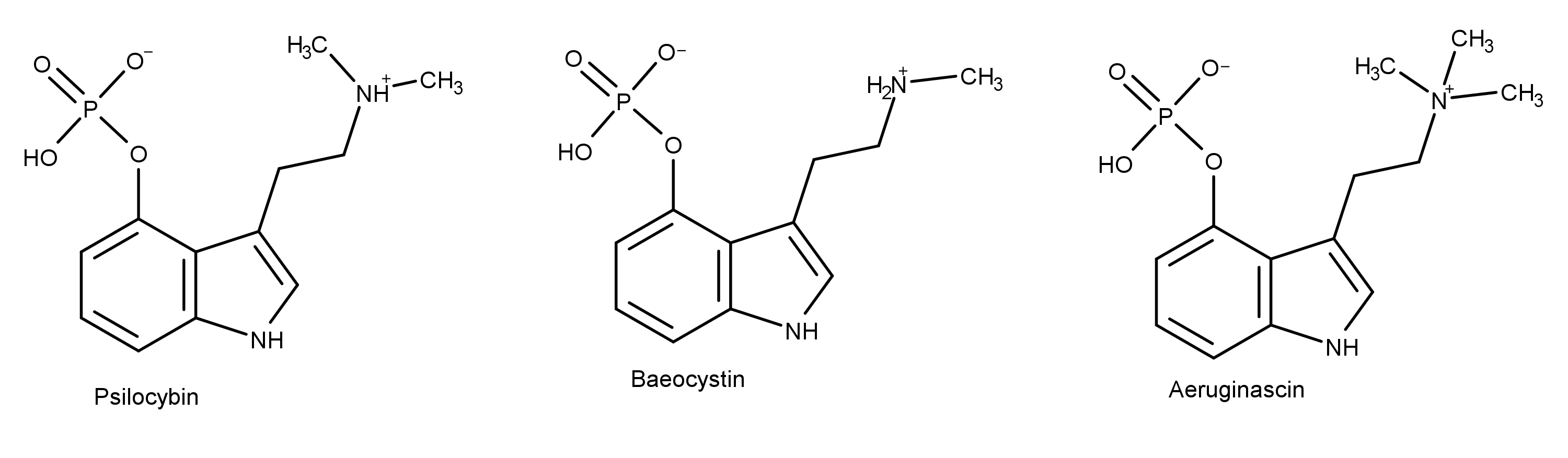

Like the other magic mushroom compounds baeocystin and norbaeocystin, aeruginascin is a compound that is structurally similar to psilocybin. Aeruginascin occurs naturally in the psychoactive mushroom Inocybe aeruginascens. In 1989, scientist Jochen Gartz found that the fruit bodies of Inocybe aeruginascens were rich in aeruginascin.1

Structurally, the molecule aeruginascin resembles psilocybin and baeocystin. It differs by having three methyl groups (instead of one or two) on the ethylamine moiety.

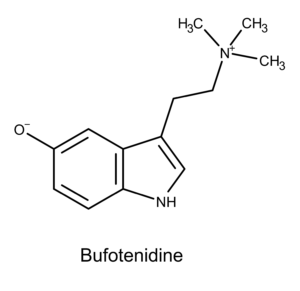

Interestingly, aeruginascin’s chemical structure is also closely related to a compound in toad secretions (aka venom) called bufotenidine. Although bufotenidine lacks the phosphate group in position 4 (instead it has a hydroxide group on in position 5) it has three methyl groups on the ethylamine moiety as aeruginascin does.

The Effects of Aeruginascin on Humans

Aeruginascin’s specific mode of action remains unstudied. In contrast to psilocybin and psilocin, ingesting aeruginascin appears to only produce euphoria as opposed to hallucinations.1

Because it is a quaternary amine, scientists hypothesize that aeruginascin cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, except when it is metabolically demethylated or when it is accompanied by a specific transporter.2 Penetrating the blood-brain barrier is important to generating the psychoactivity observed for the dimethylated analogs psilocybin and psilocin. One would expect similar logic to apply to aeruginascin.

Read a more in-depth discussion of aeruginascin in the PSR article The State of the Art of Aeruginascin – July 2019.