Ketamine has a long and varied history of medicinal use. Initially administered as an anesthetic, the compound also demonstrates therapeutic benefits in conditions such as treatment-resistant depression and substance use disorders, such as the overconsumption of alcohol.1-2 A recent study conducted at University College London provides an insight into how ketamine produces a rapid reduction in the reinforcing and motivational qualities of alcohol.3

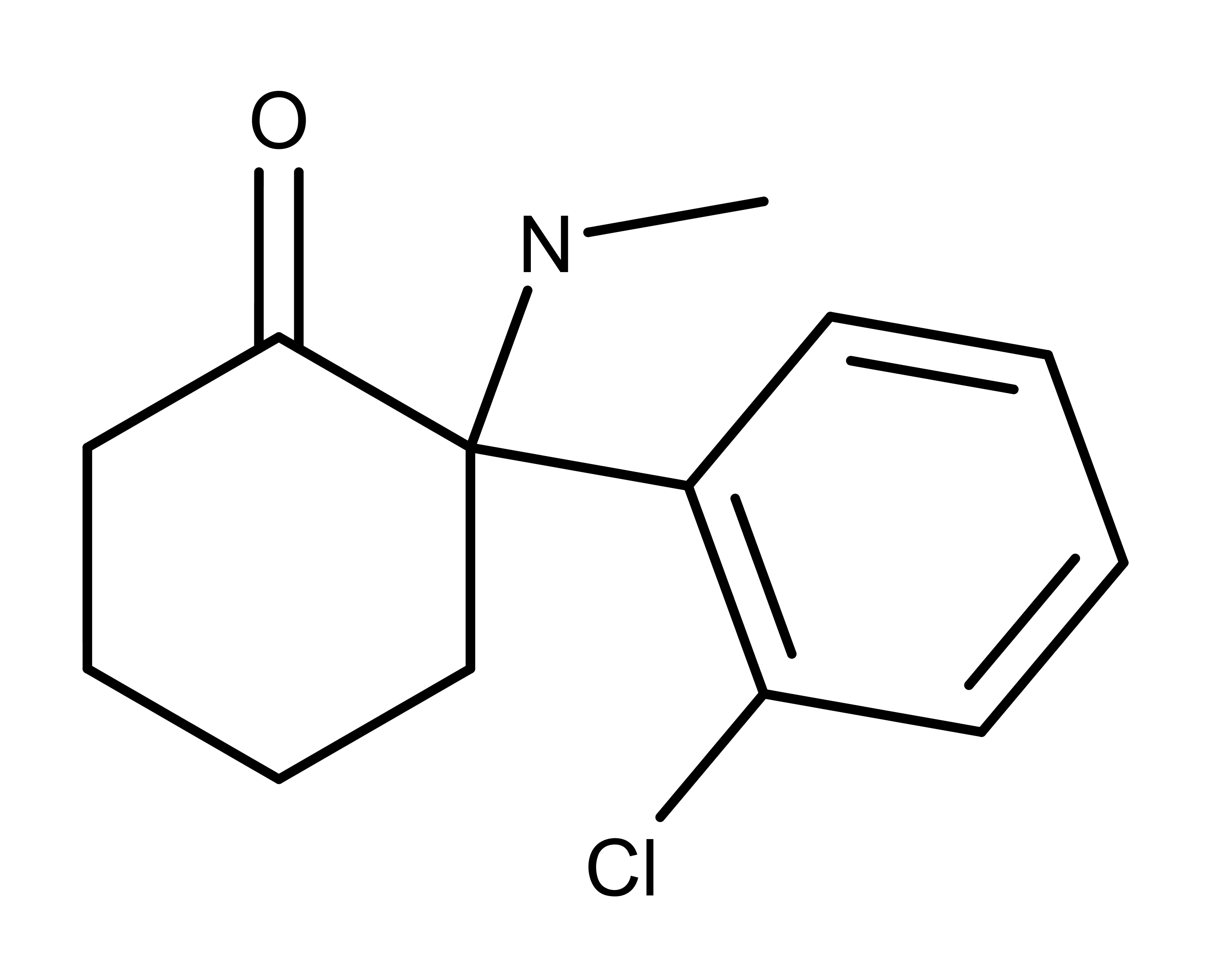

Fig 1: Chemical structure of ketamine

The Molecule and Its Effects

Ketamine is an antagonist (i.e., blocker) of the NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) receptor in neurons. Typically, the brain’s primary excitatory neurotransmitter, glutamate, binds to the NMDA receptor. However, when ketamine blocks the receptor, glutamate can’t bind to it. This blocking results in the decrease in action potential conduction velocity. An action potential is a physiological process that facilitates the transmission of signals in neurons.

Conversely, traditional serotonergic psychedelics (mescaline, psilocybin, LSD) exert their psychedelic effects through their agonist or partial agonist activity at the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor.5-6 So when studied at a cellular/receptor level, ketamine does not resemble a psychedelic compound. However, ketamine may be viewed as a psychedelic in terms of subjective experiences associated with the drug.

Ketamine causes feelings of dissociation, also called an out-of-body experience. The dissociative quality of ketamine has led to its use as a recreational drug, often referred to as “special K.”

Malleable Memories

The University College study revolves around the concept that addiction, to some degree, is a memory disorder. Individuals learn to associate drugs or alcohol with the positive feelings they bring. Specific external cues, such as the smell or picture of a beer, can trigger those memories — and cravings. Such triggers lead to an expectation of drug reward. The encoding of connections between drug/alcohol-related cues and reward are termed maladaptive reward memories (MRM).

Previously, MRMs were thought to become long-lasting once stabilized- or consolidated – into long-term memory storage, promoting relapse even long periods of drug/alcohol abstinence4. However, recent insights into the malleability of long-term memories may facilitate the rewriting of maladaptive memories. Reconsolidation involves the temporary reactivation and destabilization of long-term memories, in order to incorporate new information. Ketamine’s primary target, the NMDA receptor, is involved in the reconsolidation of memories.

By using ketamine to interfere with memory reconsolidation, it is theoretically possible to selectively target and weaken memories. The brief reconsolidation window of memory instability proposes a novel mechanism to rewrite MRMs, hopefully leading to fewer instances of relapse.

Study coauthor Ravi Das told sciencenews.org, “We’re trying to break down those memories to stop that process from happening, and to stop people from relapsing.”

The Study Design

Das and his team selected a study group of 90 (55 men, 35 women) beer drinking participants. According to the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), all participants exhibited problematic patterns of drinking. However, none of the participants were formally diagnosed with alcohol use disorder or were seeking treatment.

Participants were first shown images of beer and instructed to drink one in the lab. During the experiment, they rated their cravings for beer and enjoyment of drinking. After drinking the beer, participants reported on their urge to have another one.

When participants returned to the lab a few days later, they were divided into three groups. The first group was again presented pictures of beer to refresh their memories. To heightened memory recall strength, the researchers served the group beer but then withdrew it before participants could drink. The team carried out this maneuver to generate the element of surprise.

In contrast, the second group viewed pictures of orange juice rather than beer. Then participants in both of these groups received an intravenous (IV) dose of ketamine (350 ng/dl). A third group was shown pictures of beer but received no ketamine.

The following week, participants who had their beer memories refreshed before receiving ketamine reported a reduced urge to drink, a reduction that wasn’t as pronounced for the other two groups. Furthermore, the group that had their beer-drinking memories refreshed and received ketamine also reported drinking less.

Researchers also measured blood concentrations of ketamine and its metabolites during the reconsolidation window. This blood marker served as a surrogate for central ketamine availability. If blockade of memory reconsolidation was the process responsible for the observed decreases in drinking, blood ketamine & metabolite levels during the reconsolidation window should predict subsequent drinking in participants that were shown pictures of beer and received ketamine, but not the group that just received ketamine. This is precisely what the group observed. This observation is noteworthy as it represents a possible biomarker for treatment response in a reconsolidation model.

During the pilot studies conducted previous to this experiment, the lab observed that the efficacy of IV ketamine treatment was dose-dependent. Considering that ketamine is relatively safe even at full anesthetic doses, the authors recommended that future studies consider using higher doses of ketamine (up to full anesthesia). Higher doses would maximize NMDAR occupancy and memory interference.

Interestingly, nine months after the experiment, all participants cut their beer consumption approximately in half. This includes the group that received no ketamine. Such an across-the-board reduction may be a result of the shift in self-awareness associated with participating in a study. However, the important take away finding from this study is the initial drop in drinking amongst people who received ketamine while reminded of beer.

Future Perspectives for Ketamine

The therapeutic repertoire of ketamine is ever-expanding. However, misuse of the drug also leads to adverse effects such as delirium and confusion. Moving forward, clinicians and scientists much weigh the costs-benefit when prescribing treatment with abuse potential such as ketamine. Preliminary studies such as the one described in this article demonstrate that even a single-dose administration of ketamine can reduce drinking behavior, limiting the potential for abuse and dependency. Furthermore, this paradigm of memory interference could extend to conditions such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).