Psilocybin, a prodrug of psilocin found in magic mushrooms, has garnered significant attention as a potential rapid-acting antidepressant when delivered in the form of psilocybin-assisted therapy. The existing evidence is undoubtedly promising, but far from conclusive, as previous studies were limited by their design, small sample sizes, or were conducted in a depressed population in the context of a life-threatening cancer diagnosis.1-6

A study conducted by Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris and colleagues at the Centre for Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London, and recently published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine, attempted to build on that promise.7 It is the most rigorous assessment of psilocybin-assisted therapy for treating depression to date, but ultimately produced results that are challenging to interpret.

Study Design

The trial was a Phase II, double-blind, randomized controlled trial that aimed to assess the efficacy and mechanisms of psilocybin-assisted therapy compared with escitalopram (also known as Lexapro or Cipralex), a leading selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant, in combination with psychotherapy. The psilocybin (COMP360) was provided by COMPASS Pathways, but the study was independently designed and executed by the Imperial team.

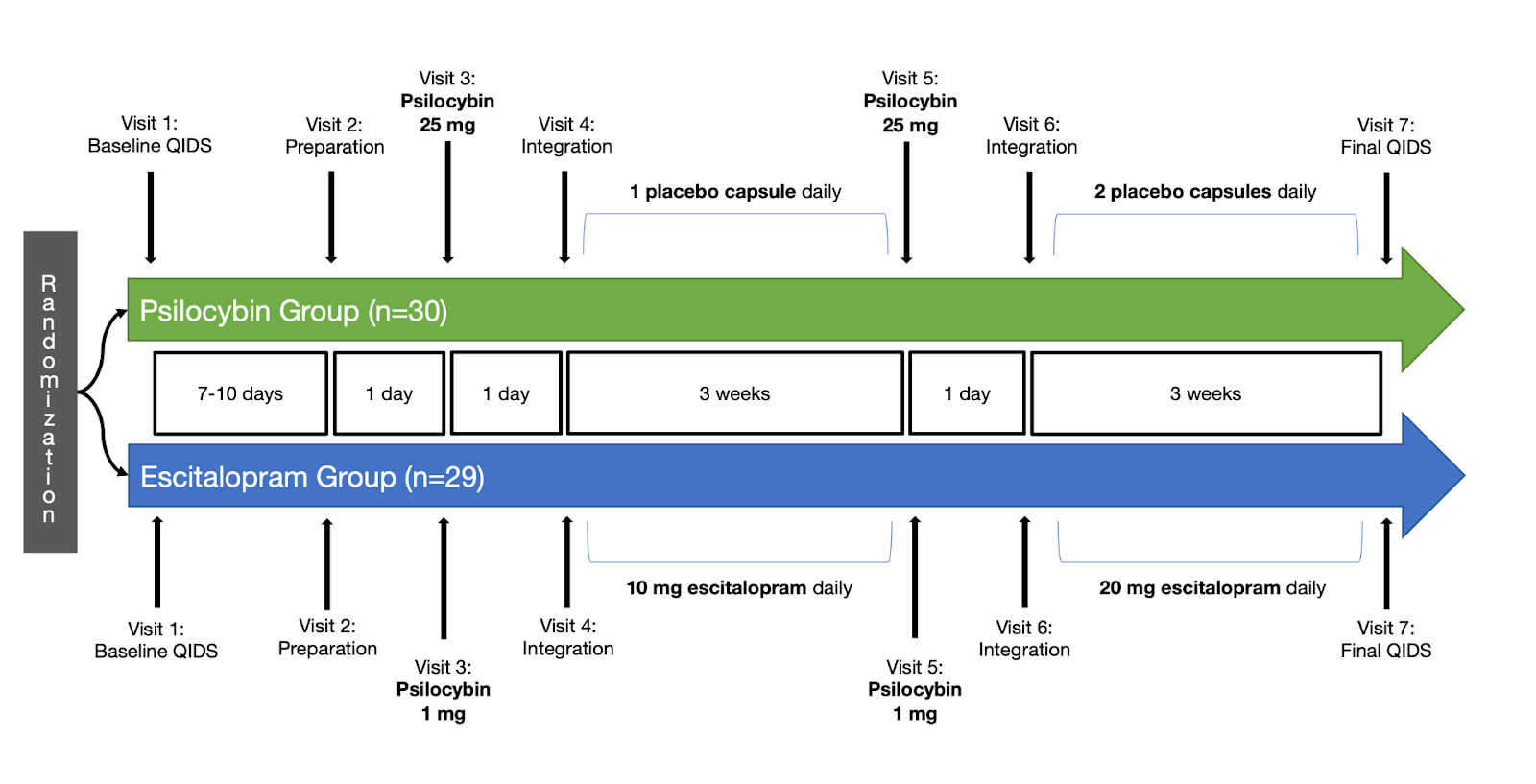

Fifty-nine participants were randomly assigned to six weeks of either daily escitalopram (10-20 mg) or placebo, interspersed with two sessions of psilocybin-assisted therapy three weeks apart (Figure 1). Psychological support based on formal psychotherapy approaches was provided to all participants before, during, and after each psilocybin session by two mental health professionals or “guides”. The dosing days consisted of participants ingesting psilocybin while laying on a bed with eyeshades and listening to a predetermined playlist to direct their attention inwards. Guides were readily available to provide support or reassurance if required.

In each session, the psilocybin group received a moderately high (25 mg) dose of psilocybin, whereas the escitalopram group received a presumed inactive dose (1 mg) of psilocybin. A similar inactive dose was used in a previous psilocybin trial, as it allows the researchers to tell study staff and participants that both treatment groups would receive an undisclosed dose of psilocybin.5 This design is intended to minimize participants’ treatment expectations, a core component of the placebo effect.8

FIGURE 1: Click to enlarge. SIMPLIFIED PROTOCOL OVERVIEW. NOT PICTURED: ONE PREPARATORY PHONE OR VIDEO CALL PRIOR TO VISIT FIVE, SIX TOTAL INTEGRATION CALLS (THREE AFTER EACH PSILOCYBIN SESSION), FUNCTIONAL MRI ASSESSMENTS AT VISITS TWO AND SEVEN, AND ALL SECONDARY OUTCOME MEASUREMENTS. Image CREATED BY MICHAEL HAICHIN.

The pre-registered primary clinical outcome was the score difference from baseline to week six on the self-rated 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Report (QIDS-SR-16).9 Pre-registration is a public declaration of the study design before it begins, and functions to prevent publication bias (the tendency for negative results to remain unpublished) and selective outcome reporting (researchers selecting favourable results for publication) — neither practice is uncommon in antidepressant research.10

Secondary outcomes, which were not pre-registered, consisted of other validated depression scales, including the Beck Depression Inventory 1A (BDI-1A) and the clinician-rated Montgomery and Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D-17). Additional measures related to depression, such as anxiety, wellbeing, suicidal ideation, and work and social functioning, were also recorded.

Results

The psilocybin and escitalopram group consisted of participants with mild to severe depression and an average duration of depression of 22 and 15 years, respectively. No serious side effects were recorded, and the rate of side effects was similar in the two groups. Participants in the psilocybin group most frequently experienced transient headaches within 24 hours after the psilocybin sessions, while those in the escitalopram group had more anxiety and dry mouth.

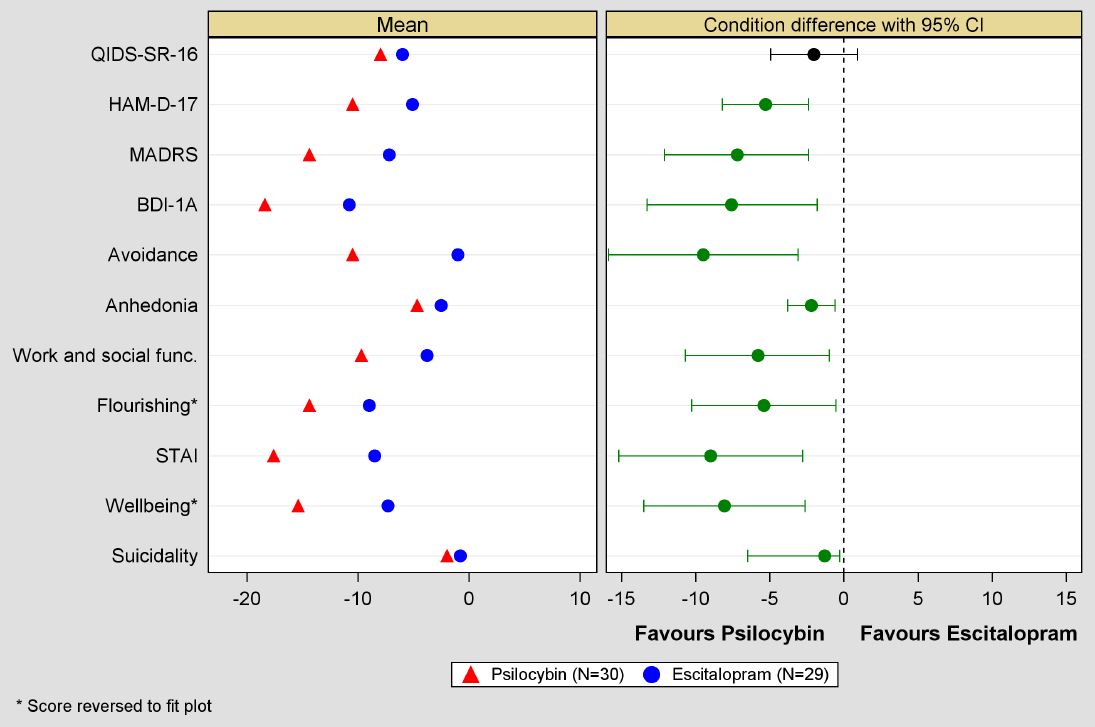

The average decrease in QIDS-SR-16 score after six weeks was eight points in the psilocybin group and six in the escitalopram group, both considered clinically significant improvements in depression. However, with a between-group difference of two points, there was no statistically significant difference between the two treatments, meaning the difference was small enough that it might be the product of chance. Based on that result alone, some might suggest the promise of psilocybin-assisted therapy appears partly unfulfilled.

But the secondary outcomes paint a different picture. Remission of depression occurred significantly more in the psilocybin group with 17/30 (57%) participants compared to 8/29 (28%) of those taking escitalopram. The other scales used to assess depression severity, as well as those for anxiety, wellbeing, and several other factors all significantly favoured psilocybin over the six-week trial period (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2: Click to enlarge. PRIMARY AND SECONDARY OUTCOMES COMPARING PSILOCYBIN AND ESCITALOPRAM GROUPS AT WEEK SIX.7 GREEN CONDITION DIFFERENCE = STATISTICALLY SIGNIFICANT. STAI = STATE-TRAIT ANXIETY INVENTORY.

What Does It All Mean?

When there is no significant difference between groups on the primary outcome measure, typically a trial is considered negative, and the secondary outcomes are considered exploratory. However, in this case, where the trial was likely too small to detect psilocybin’s potential superior treatment effects, it is appropriate to describe the findings as inconclusive, rather than negative for psilocybin.11 Despite the positive findings in favour of psilocybin with the secondary outcomes, they were not pre-registered and lacked necessary statistical adjustments, so limited conclusions can be drawn from them.

Failing to establish statistical superiority, while avoiding being statistically worse on the primary outcome does not mean it is appropriate to conclude that psilocybin-assisted therapy is as effective as combined escitalopram and therapy. This is because the study was not designed to test whether psilocybin is equivalent to the escitalopram group. This would require pre-specifying the margin by which the two interventions can differ from each other in either direction. But given that this was a relatively small Phase II trial, these results also do not mean that psilocybin is not in fact an equivalent or even superior antidepressant as anticipated, simply that further research is required.

Is psilocybin being 21 times as efficient at delivering those outcomes not a statistically significant difference between the two treatments?

I don’t disagree about the effectiveness here.. but it’s not 21x.

Their best statistic showed a 29 percent increase in terms of efficiency. So the math dictates a 2.9x increase of effectiveness/efficiency. Or more closely to your number, if you adjusted the math it would be 2.1x better.