Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) was first synthesised by Richard Manske in 1931.1 However, its psychoactive properties in Western medicine were not discovered until self-administrative experimentation by Dr Stephen Szara in 1956.2 This discovery contributed to the explosion of research regarding psychoactive compounds at the time, but like many in this class of drugs, its history of use in clinical trials has been turbulent.

From Tree to Trial: Self-Administration Experiments

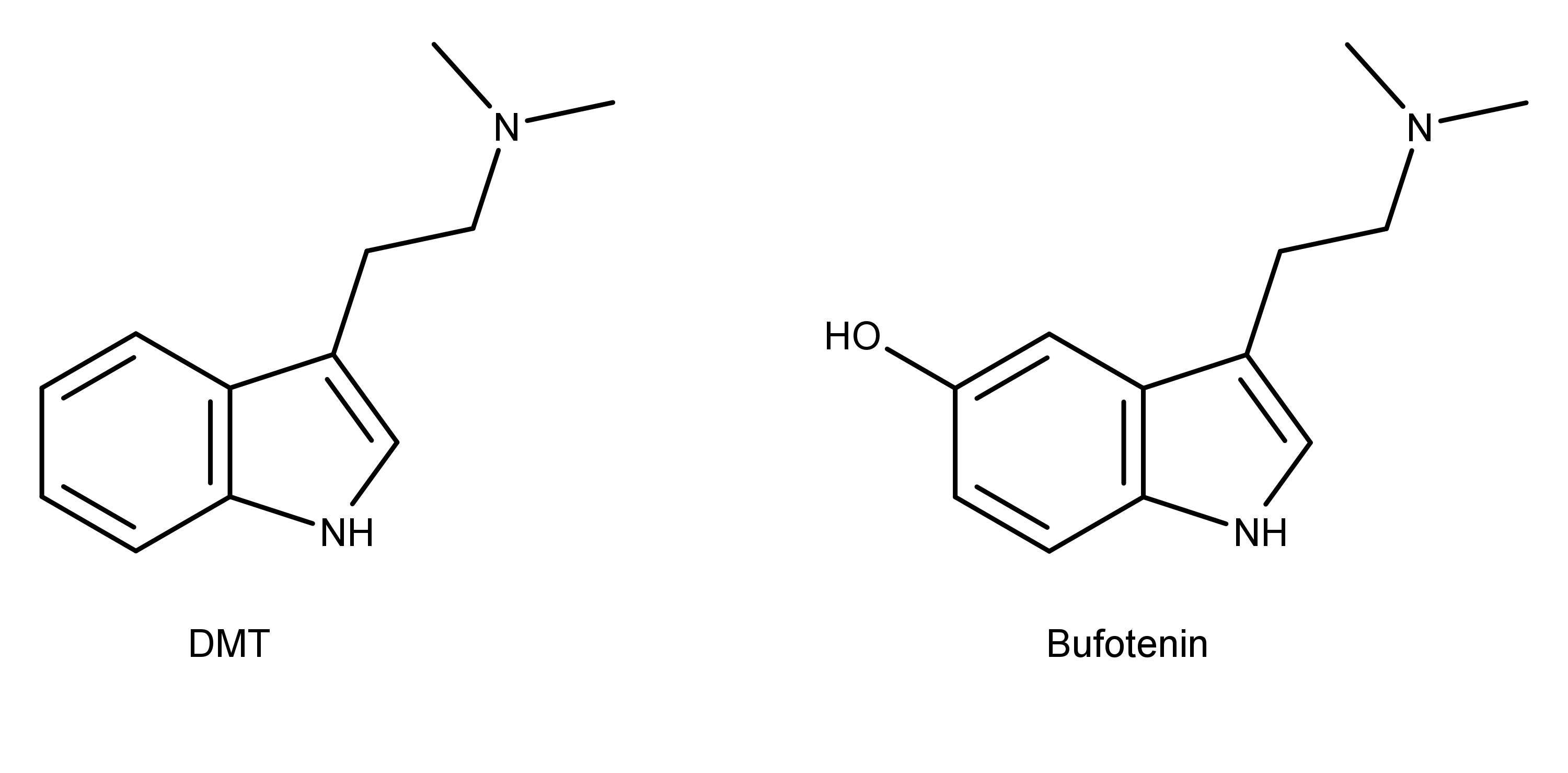

The seeds from the perennial tree Anadenanthera peregrina, long used by South American tribes in the preparation of ceremonial hallucinogenic snuff, were found to contain both bufotenine and DMT.3 At the time, out of these two compounds, only bufotenine was known to possess hallucinogenic inducing properties.4 The presence of DMT within the seeds and its highly similar chemical structure to that of bufotenine alluded to the fact that DMT may also induce similar effects. To explore these effects in humans, Dr Stephen Szára carried out the first human trials using synthesised DMT initially through self-administration experiments2 and eventually progressing to a group of healthy volunteers.5

Through an initial series of self-administration trials taking DMT orally in March 1956, Dr Szára quickly found that the compound did not elicit any observable effects (unknowingly due to enzymes rapidly breaking down the DMT), even up to very high doses of 150 mg. In an effort to subvert the rapid breakdown, succeeding trials were administered intramuscularly, starting with 30 mg of DMT. This concentration was enough to result in observable pupil dilation and mild disturbances in perception, with the effects far more evident when the dosage was increased to 75 mg.2

Within 5 minutes of administration of the higher dose, Dr Szára noted a distinct physiological response of tingling sensations, increased pupil dilation, and an elevation in blood pressure and heart rate. These sensations were accompanied by visual hallucinations consisting of icons, colourful geometry, and mask-wearing entities. At the peak of his experience, involuntary hand movements were present, and his ‘visual space’ was completely filled with optical hallucinations to the degree where he could not describe what was in his immediate surroundings. After 45 minutes, most of his ‘symptoms’ had largely subsided, and thus, he was able to describe his subjective experience.2

When compared to other psychedelic compounds such as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and mescaline from his previous experiences, Szára noted that the effects arrived and dissipated in a ‘wave-like form’ though the duration and the intensity of each compound differed. Specifically, the DMT-induced symptoms were rapid in onset but had a relatively short duration compared to other psychoactive compounds.

A study in 1955 showed that in rats, DMT is broken down by amine oxidase enzymes with 3-indoleacetic-acid (3-IAA), the main product produced.6 Dr Szára found 3-IAA in both his blood and urine samples, with the concentration of 3-IAA rapidly increasing after just a few minutes and returning to normal levels after around 90 minutes. Overall, there was a distinct lack of any unaltered DMT in the urine, thus supporting the idea that DMT is rapidly broken-down following administration and provides an explanation of the brevity of the experience.

Dr Szára lastly noted that DMT invoked a unique euphoric response within him compared to other psychoactive compounds such as LSD, which resulted in heightened anxiety.

The First Group Trials of DMT

Upon Dr Szára experiencing first-hand the effects of DMT and demonstrating its relative safety, within months the trials progressed to a group of healthy volunteers.5

An intramuscular injection (0.8 mg/kg) of DMT was administered to a group of male and female medical professionals between the ages of 20 and 42. Subjective accounts experienced by the volunteers were recorded by Dr Szára alongside measurements of blood pressure, heart rate and pupil dilation.

Effects were felt as early as three minutes by several participants with some experiencing illusions, hallucinations, and waves of euphoria. Alterations of body perception and sensory stimuli, depersonalisation, and involuntary movements were also noted.

Verbatim remarks were also recorded with reports from one participant including: “Everything is brighter, the whole world is significantly brighter” and “’Oh, a new wave! The pictures come in such quantities that I do not even know what to do with them!”.

Some physiological parameters were relatively consistent across all volunteers (including the experiments Dr Szára conducted on himself) such as slight elevation in blood pressure and heart rate, vegetative symptoms including loss of awareness, dilation of the pupils, and intensification of visual hallucinations with closed eyes.2,5 The rate of DMT metabolism in the form of 3-IAA concentration collected from the urine of volunteers was consistent with the analysis of the blood and urine of Dr Szára’s self-experiments.2,7 This further supports the rapid yet short experience that DMT induces.

The early experiments conducted in the late 1950s highlighted the relative safety of DMT, its potent hallucinogenic inducing effects, and the high degree of consistency regarding the symptoms it induces across different people. This work laid the foundation for future trials carried out by Dr Szára8 and also more recent clinical research from teams led by Dr Rick Strassman in the early 1990s9,10 and Dr Robin Carhart-Harris in the late 2010s.11–13

UK Starting First DMT Clinical Trials to Treat Depression

In partnership with Dr Carhart-Harris at the Centre for Psychedelic Research, Imperial College London, Small Pharma will soon be carrying out the first DMT clinical trials of its kind in the UK. Over 60 volunteers are enrolled over both phases of the trial which aims to assess the safety, tolerability, and how the drug is broken down in volunteers both healthy and those suffering from Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). A series of objective and subjective measurements are to be carried out similar to previous trials though this is the first study to evaluate the effectiveness of DMT-assisted psychotherapy in those living with MDD (Alex Whiteman, BSc, email communication, January 2021).

Conclusion

Clinical research regarding DMT has been intermittent since its initial discovery, largely due to political hurdles preventing the study of the compound. These early published studies have shown the relative safety of DMT, and now finally researchers are working to further interrogate the effects of these compounds in a therapeutic context.

Wow, great article, thanks for the publication!

The drink of the natives of the Amazon, contains dmt, in the chacruna plant. The second plant, cipó mariri, contains MAOI, it is not known how the natives arrived at this mixture. natives of the northeast region of Brazil found another plant with dmt, the jurema-preta.

it appears that DMT is not active on its own through oral ingestion, as explained in this article. however, through the respiratory tract it appears to be active, the jurema-preta appears to be smoked, the bark of the tree.