Psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (PAP) holds promise as an effective treatment for a wide range of psychological disorders.1 Researchers and clinicians have become increasingly interested in identifying the PAP mechanism of action to elucidate the key components of the treatment approach that produce positive therapeutic outcomes.

Different psychotherapeutic modalities have unique mechanisms of action. A psychotherapeutic mechanism of action refers to the processes by which therapeutic change occurs.2 These processes may be considered from the neurobiological and or psychological perspectives.1

More recently, and with advances in brain imaging technology, researchers have focused on the neurobiological mechanism of action or the changes that occur in the brain to produce the PAP therapeutic effect. For example, researchers have identified functional brain connectivity as involved in the effectiveness of PAP.3 Despite greater attention paid to the neurobiological mechanism of action of PAP, mechanisms of neurobiological and psychological action are undeniably interdependent.

The Mystical Experience and the Psychological Mechanism of Action of PAP

As PAP gains traction as an efficacious treatment for a wide range of mental disorders, there is a renewed interest in understanding psychological mechanisms of action via patient reports of therapy experiences. One common patient report, with an established connection to PAP efficacy, is the mystical experience.1

The mystical type experience is understood as an important factor contributing to change in PAP. Yet, the specific psychological mechanism by which the mystical experience elicits change remains unclear. In an attempt to describe the underlying mechanism of change of the mystical experience in PAP, researcher Peter S. Hendricks looked to the extant literature on the discrete and complex emotion, awe.1

Awe and the Mechanism of Change in PAP

Awe is defined as an emotional response to perceptually vast stimuli that transcend one’s schema, or frame of reference. In other words, there are two specific cognitive appraisals are necessary for the emotion of awe to be experienced: 1) perceived vastness, and 2) a need for accommodation.4

Perceived vastness means the perception of stimuli as being larger than the self, or perceiver. To integrate this experience, the perceiver must shift internal psychological structures, or make an accommodation, for the new information about the self in relation to the world. In short, according to Peter Hendricks: “awe might be expected to occur whenever one encounters something perceived as so vast and novel that he or she has to change the way he or she views reality.”1

Awe is an uncommon emotion in everyday experience, yet commonly evoked during the course of PAP, and associated with profound mystical experiences. In the context of mystical experiences, awe has the function of inducing an experience of small-self or ego dissolution.1 This experience is associated with a sense of interconnectedness or oneness with others and the world, attentional bias outward and beyond the self, as well as cooperative prosocial behavior, and even the perception that one’s physical self is smaller in size.1 As a psychological mechanism of change, awe, as evoked in the mystical experience, has been generally overlooked by researchers and clinicians, until now.

The Theoretical Model: Awe in the Mystical Experience and Acute and Long Term Benefits

Awe is an emotional signature of the mystical experience as reported by PAP participants on self-report measures and in less formal clinical interviews.1 As noted previously, the emotion of awe in the mystical experience is linked to the experience of small-self, which can yield profoundly meaningful shifts in self-concept associated with positive psychological change, in both the acute and long-term.

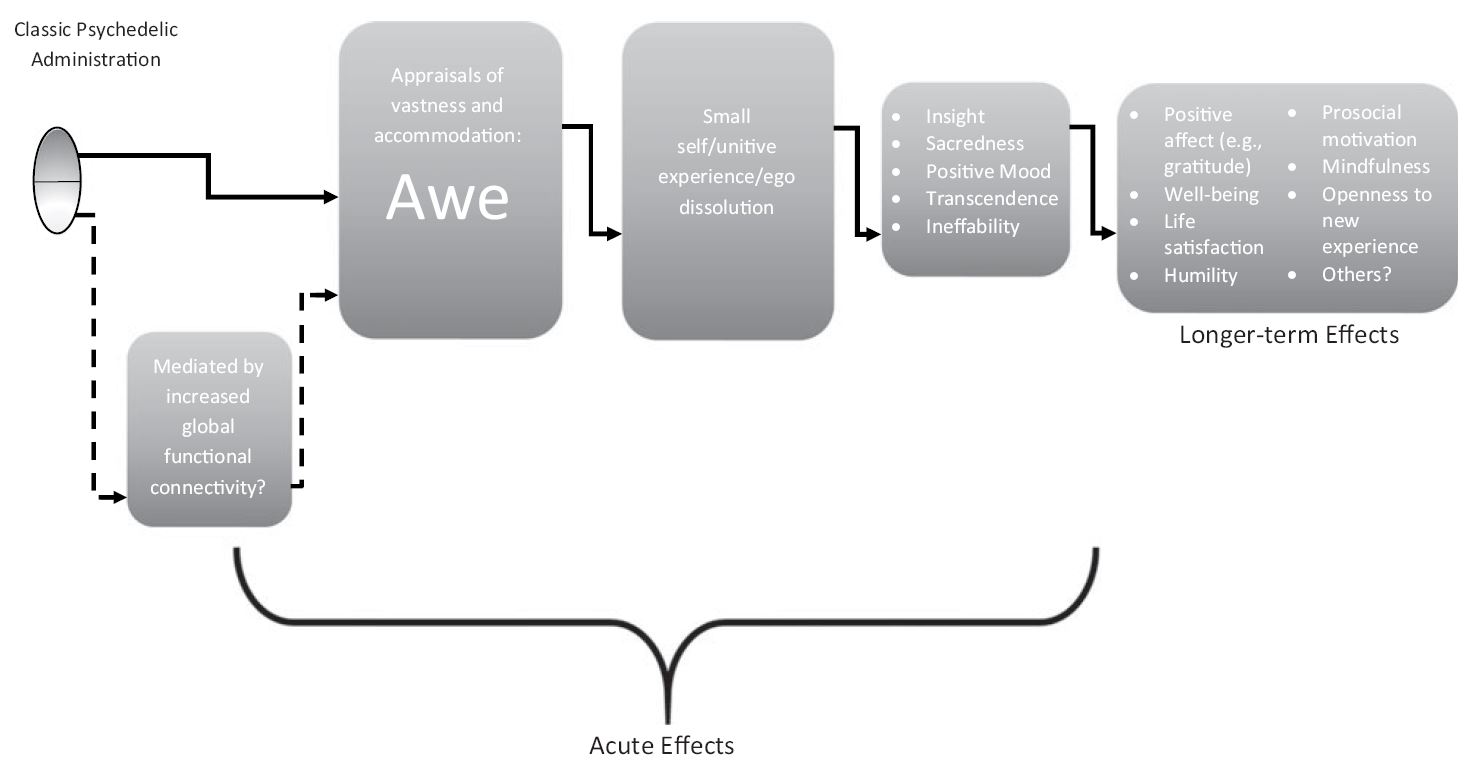

According to Hendricks’s review of the awe literature, the acute short-term therapeutic benefits of awe-induced small-self include insight, sense of sacredness, positive alterations in mood, and experiences of transcendence.1 In the long term, positive psychological benefits include experiencing more positive affect, a greater sense of well-being, increased life satisfaction, humility, as well as prosocial motivation, mindfulness, and openness to new experiences. Hendricks outlined his proposed mechanism of action involving awe, the mystical experience, and the acute and long-term benefits via a conceptual model, represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Click to enlarge. Proposed psychological model of classic psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.1

Conclusion

Researchers and clinicians in the field of mental health have long been interested in the underlying mechanisms of change in psychotherapy. As a result, numerous psychological processes, including emotional processes, have been studied to clarify their involvement in therapy change processes.

The complex yet distinct emotion of awe is a common feature of the mystical-type experience frequently reported by participants in PAP. Awe, in the context of the mystical experience, rises from drug-induced alterations in perception to yield the experience of small-self, which has numerous therapeutic benefits, both short-term and long-lasting.

With a broad model for understanding the role of awe in PAP now elucidated, further research can clarify the more granular mechanisms by which awe induces the experience of small-self and subsequent downstream effects in terms of positive therapeutic benefits. Further research exploring the intersection between awe, the mystical experience as well as personality and neurobiological factors may further clarify the PAP psychological mechanism of change and potentially enhance its effectiveness.