History of MDMA and Entactogens

Entactogens, also known as empathogens, are a group of drugs related to MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) and are mainly comprised of various amphetamines that are best known for their ability to induce states of heightened empathy, feelings of closeness with others, diminished inhibitions, and euphoria.1,2 Entactogenic drugs, specifically MDMA, rose to prominence in the 1980s and ‘90s as “club drugs” often consumed recreationally at concerts, raves, and other social gatherings for their prosocial and mild psychedelic-like effects. However, MDMA and the closely related MDA (3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine) had been developed and studied long before they found their way into the club scene.

First developed over 100 years ago by German chemists, the effects of the prototypical entactogens MDMA and MDA were initially studied by Gordon Alles in conjunction with the pharmaceutical company Smith, Klein & French (SKF) as treatments for a myriad of conditions.3,4 Following an initial period of research by SKF and the United States government in the 1940s and ‘50s, MDA was used for recreational and spiritual purposes by groups associated with the counterculture movements of the ‘60s. Around this same period, MDMA was popularized by the prominent psychedelic chemist Dr. Alexander “Sasha” Shulgin as a tool for use in psychotherapy. Thanks in large part to the pioneering work of several scientists and psychotherapists including Dr. Shulgin and his wife Ann, Dr. David E. Nichols, and Dr. Leo Zeff, MDMA was soon adopted by many in the psychotherapy community as a tool for facilitating communication and healing in the context of therapy.5,6

By the early 1980s, MDMA had begun to spread beyond the niche communities of psychedelic users, academics, and psychotherapists interested in its unique psychoactive effects. The growing awareness of MDMA’s desirable prosocial effects led enterprising groups in several US cities to begin producing tablets containing the drug for use in clubs, bars, and the nascent electronic music scene, where it was dubbed ecstasy or ‘XTC’.7 Unfortunately, once MDMA became associated with recreational use and the controversial electronic music scene, it caught the attention of authorities who moved to place the drug in schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA).

The proposal to label MDMA as a dangerous drug with no medical value led to significant pushback from the psychotherapeutic community, who had been informally studying the drug for years and gathering evidence of its therapeutic utility. However, in spite of the outcry from mental health professionals and subsequent testimony in DEA hearings on MDMA’s therapeutic value, the DEA decided to move forward and the drug was formally scheduled in 1985.8 Following the DEA’s unilateral decision, research into MDMA’s therapeutic uses was abandoned for decades until interest was revived by the efforts of organizations such as the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS).9

MDMA Pharmacology

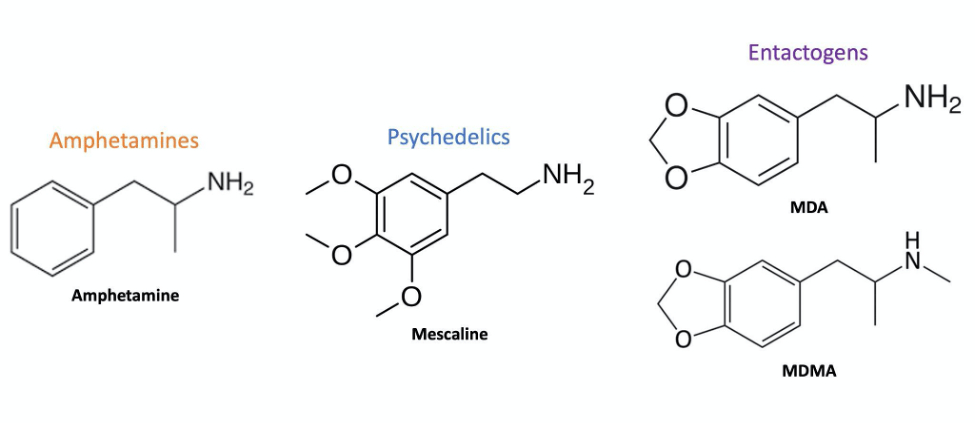

Figure 1: Chemical structures of prototypical members of the amphetamine, psychedelic (mescaline), and entactogen (MDA & MDMA) families. Note the common phenethylamine structure shared by all three families and the combination of features that MDA & MDMA blend together from both amphetamines and psychedelics. Created by Harrison Elder.

Despite suffering an extended hiatus from clinical use, the widespread popularity of MDMA over the last 30 years encouraged extensive research into its pharmacology and behavioral effects. Studies on MDMA’s mechanism of action demonstrated many pharmacological similarities with other members of the amphetamine class, as well as psychedelics (Figure 1). Like other amphetamines, MDMA acts as a releaser of dopamine (DA), norepinephrine (NE), and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT) by acting on neurons to cause their release into the synapse.10–12 However, MDMA’s unique prosocial effects were found to come from its bias towards releasing serotonin unlike typical amphetamines, which preferentially affect dopamine and norepinephrine.13

Additionally, MDMA was found to interact directly with serotonin receptors such as 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT2C in a manner similar to psychedelics, further setting the drug apart from others in the amphetamine family.14,15 The combination of these disparate mechanisms makes MDMA a pharmacologically unique drug with effects that are greater than the sum of its amphetamine and psychedelic parts. Consequently, MDMA and related serotonin-biased releasers are increasingly considered to belong to a class of their own, dubbed entactogens (from the Greek “to touch within”) or empathogens (giving rise to empathy).2

Present Research

Medical interest in entactogenic drugs has undergone a revival over the last decade due to the enduring efforts of organizations such as MAPS, who have fought for the ability to investigate MDMA-assisted therapy as a treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Entactogens may be beneficial as adjuncts to psychotherapy because of their ability to lower inhibitions, facilitate non-judgmental introspection, and enhance feelings of trust and closeness with therapists.16,17

For disorders like PTSD, such a tool allows patients to feel safe while being emotionally vulnerable with their therapists, further allowing them to revisit traumatic memories without incurring strong negative reactions that may hinder progress. Additionally, MDMA therapy may be effective for treating PTSD due to pharmacological actions beyond those that are felt subjectively. These include its ability to influence neurological processes involved in fear extinction and memory reconsolidation via modulation of key stress hormones such as cortisol and oxytocin.21

Despite the considerable legal and societal hurdles involved in conducting clinical research on schedule I drugs, MDMA has produced impressively positive results in the treatment of PTSD thus far. Results published in 2011 from a phase II pilot study of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy found it produced PTSD remission in 10 of the 12 subjects who received two MDMA sessions.9 The results of this study were subsequently pooled with results from five other phase II trials, which led the FDA to grant it Breakthrough Therapy Designation in 2017.9,18-22

Unfortunately, the optimism surrounding recent clinical successes was tempered by allegations of sexual misconduct and the use of flawed research practices in those trials. In the podcast Cover Story released between March and May of 2022 by New York Magazine, some participants recounted instances of inappropriate behavior by therapists, increased suicidality after treatment, and unsound reporting practices that had occurred during their involvement in the trials.23,24

At present, one phase III clinical trial is currently underway and one phase III trial recently concluded, the results of which support the safety and efficacy of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy.25 Considering that phase III trials are typically the final stage of evaluation required before a drug can be approved for medical use, it seems likely that MDMA may soon complete its journey from the counterculture to the clinic counter, shedding its stigma to find its place in modern medicine.

This article was updated on July 25, 2022 to include reference to the various issues raised by the Cover Story podcast.

Great write-up, Harrison!

I was wondering what you thought of MDMA and MDA potentially being neurotoxic. I believe some primate studies have found a loss of 5-HT in cortical and hippocampal areas after administration (Molliver, M. E., Berger, U. V., Mamounas, L. A., Molliver, D. C., O’Hearn, E., & Wilson, M. A. (1990). Neurotoxicity of MDMA and related compounds: anatomic studies. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.). How do you think this might factor into the FDA’s decision-making process? Do you know of any longitudinal safety studies underway? Has an optimal dose been established in clinical trials?

Hi Cameron, Glad to hear you enjoyed the article! The neurotoxicity of MDMA remains one of the most hotly debated and complex topics in the field, and likely deserves an entire article of its own. While some early studies suffered from methodological issues and misreporting (see withdrawn studies by Ricaurte et al), there is a consensus in the scientific community that MDMA and MDA can be neurotoxic to dopaminergic and serotonergic neurons under certain circumstances. If you’re interested in the mechanisms and factors underlying MDMA’s neurotoxic effects I found this to be a solid recent review: (Costa G, Gołembiowska K.… Read more »

You left out that one participant in a clinical trial was raped by her therapist while she was still enrolled in the trial, and that a number of MAPS MDMA trial participants became acutely suicidal during or directly after the study. You also left out the official reports fail to discuss or even report these serious issues. You also left out that the drug effects and the hype around the trials affects how participants respond to the outcome measures which seriously jeopardizes the validity of the efficacy data being produced. You also left out that the Phase 2 data on… Read more »

Thank you for taking the time to comment and share more information. As you mentioned, it has recently come to light that some potentially serious misconduct and oversights have occurred in MAPS-sponsored MDMA trials. Unfortunately, discussing the issue of MDMA trial integrity was not within the scope of this specific article and requires an in-depth and nuanced review of its own. As such I would encourage anyone interested in these recent developments to check out the reporting by New York Magazine’s Cover Story podcast. Some of these developments, specifically those relating to Health Canada, are ongoing and therefore more appropriately… Read more »

This is a little unfair. Not every article about MDMA-assisted therapy has to focus on the abuse stories. It’s not “omission,” it’s different articles having different topics. Other articles on this site have thoroughly discussed everything you mentioned. If you assume bad faith everywhere, you will miss out on people who are actually on your side.